How the 6 Principles of Pilates Align Perfectly with Physiotherapy

Hey! I'm Physio Ellen

Sharing the joys of Clinical Pilates with my clients is what keeps me fueled.

It would be my pleasure to show you the ins and outs so your own clients can benefit, too.

Grab my free Reformer Rehab Integration Guide

March 19, 2025

Unless you’ve taken a Pilates teacher training course, it’s unlikely that you’ve heard of the 6 Pilate principles. For the uninitiated, Pilates was created for therapeutic purposes. This seems far from its current-day image of women in sports bras surrounded by Instagram-worthy spaces.

Learning about the principles provides insight into how holistic the original Pilates method really is. The 6 principles beautifully interweave all three major physiotherapy streams, namely Orthopedic/Musculoskeletal, Neurology, and Cardiorespiratory practice. If you know me at all, I’m constantly plugging the benefits of Pilates for rehab, but I want share just how deeply rooted it really is. Whether it’s Mat, Reformer, Chair, Cadillac, or any other piece of Pilates equipment, the principles still apply to every movement.

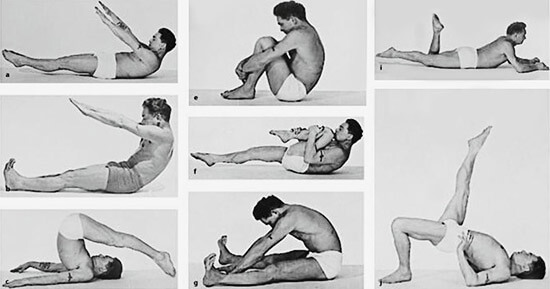

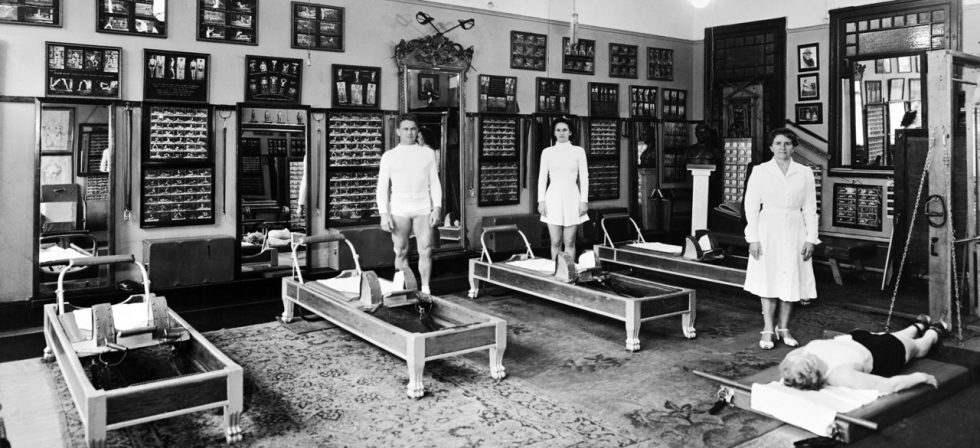

Joseph Pilates referred to his method as Contrology, and the name change only occurred after his death. To be accurate, his closest students distilled the following principles from his teaching philosophies to help preserve the spirit of his method.

- Breathing

- Concentration

- Centering

- Control

- Precision

- Flow

Breathing

Breathwork is a key characteristic of Pilates. Cues for timing inhale and exhale are explicitly indicated throughout the original exercise descriptions in Pilates’ writings. Deep inspiration is often encouraged not only for improving focus but oxygenation. Having the core control to maintain transversus abdominus support for high-level exercises while breathing from the ribs is essential when performing higher level work.

With all the known benefits of proper breath mechanics including vagus nerve stimulation/parasympathetic drive, shoulder girdle function, rib mobility, and my favourite, transversus abdominus activation, breathing is an easy principle to appreciate as a movement professional.

Concentration

Joseph Pilates strongly believed in mind-body-spirit connection. His quotes include themes of mindfulness when performing his exercises to reap the most benefit. Bringing focus to a controlled movement helps develop better body schema and proprioception.

In my opinion, discovering or rediscovering the intricate movements of our bodies is a foundational step in rehabilitation. Without a clear map in our minds, how can we hope to make changes and improvements? It’s why teaching reverse Kegels before standard Kegels is so often recommended. Subsequently, sharpening proprioceptive skills is dependent on focus and mindfulness when practicing movement.

Centering

Centering is probably the most obvious of all six Pilates principles. A large number of Pilates exercises are spine and core-centric. We often think of Hundreds as the poster child for Pilates (you know, that exercise where you’re in a V-sit with arms pulsing). Joseph Pilates recognized the importance of the core long before it became a buzzword. He spoke of the core as the ‘Powerhouse’ of the body.

Remembering back to my neurorehabilitation days, the pelvis being the foundation of the body has always stuck with me. It’s the base from which we draw stability to provide mobility to the spine and limbs. Moving without a stable foundation is akin to running in sand. Sure, you’re moving, but it’s not efficient and it’s not fun.

A solid core is not only necessary for proper strength generation but also for maximizing reach/ROM. I’ll never forget what my husband’s cousin, an Olympic track athlete, told me: Adding pelvic floor work gave her a pace a noticeable boost. It’s a perfect anecdote for how crucial the core is for peak function. And what other exercise is more touted for transversus abdominus and pelvic floor strengthening than Pilates?

Control

Before diving into the principle of Control, it’s important to differentiate Classical Pilates from modern Pilates. Pilates was never intended to be performed quickly nor without thought. True Pilates execution should be deliberate, low-intensity movement.

Building on the principle of Concentration, the concept of Control extends more to the efferent parts of the movement pathway. Moving at a slower pace better facilitates changes to movement patterns, upregulation and downregulation of muscles. Support from various Pilates apparatuses also provides clients with more opportunities to focus on changing one muscle group, limb, or joint at a time.

Thinking back to my neurorehabilitation days when working on normalizing motor patterns, establishing proper movement required slow and deliberate practice (unless you’re accessing central pattern generators, that’s a whole other thing). Learning or relearning any task will almost always be simpler when slowing it down. It seems that Joseph Pilates understood this, and it’s also why I often cue for slower pacing when my clients learn a new exercise.

Precision

I don’t teach group classes. Nothing against classes, because they make Pilates accessible to more people compared to expensive private sessions. However, my biggest concern with running them from a therapeutic perspective is quality control.

I once taught a few group classes to some coworkers when I worked at a hospital and I can’t say it was an overly positive experience. I have this clear memory of someone saying it was easy. Meanwhile, nearly everyone else was sweating and talking about burning muscles. All this to say, Pilates without proper form and precision is nothing at all.

Every time I coach a client through an exercise, I want to know where they are feeling it in their body. Every. Single. Time. If it’s not in the desired muscle group, that means I need to do something about it. That’s where proper Pilates training is so valuable.

From a neurological perspective, this concept also extends to selective movement and dissociation/isolation. Can someone access the correct joint/muscle? Can they move without compensatory strategies? Is the movement accurate (I’m looking at you, heel-to-shin test)?

To be able to analyze and adjust is something we already do as physios. Pilates is no different.

Flow

Pilates has a strong foundation in dance, specifically ballet, that is evident in many of the exercise names such as developé, arabesque, and port de bras. While movement quality with Pilates should aim to be smooth, coordinated, and graceful, it’s no easy feat.

Ballet is any extremely physically demanding form of dance despite how effortless it appears to be. Similar to elite sports, finesse and fluidity require control, strength and efficiency. This builds on the principle of Centering, where a solid core is needed to move with skill.

In a clinical setting, I explain this concept to my clients as the need for a stable base in order to have a free-moving limb. To put it more simply, it’s like building a construction crane on sand and expecting it to work efficiently.

When a high-level athlete or dancer makes something look easy, it becomes apparent that they operate with expertise. There is no guarding of muscles in the shoulder girdle or clenching in the glutes.

Closing Thoughts

No matter which area of physiotherapy or rehab you work in, I hope it’s clear how all six Pilates principles are interconnected, not unlike physiotherapy; you fix one area/system to help fix another e.g., addressing breath pattern to improve core stability and shoulder girdle alignment.

I’m seeing increasing overlaps among specialties such as women’s health, sports physiotherapy, neurology, etc. Physiotherapy itself is expanding and evolving to be more holistic by including aspects such as mental health and mindset. Healthcare in general is breaking out of its silos and I’m looking forward to seeing where it leads.

It is true that Joseph missed the mark with some of his beliefs (he felt the perfect spine should hardly have any curves). However, his general concepts and exercises have been safely updated while still providing joy. If we can get our clients moving more by offering a fun and engaging treatment option, that’s a great thing.

Have I piqued your interest in adding Clinical Pilates for your skill set? See my course page for more information.

leave a comment